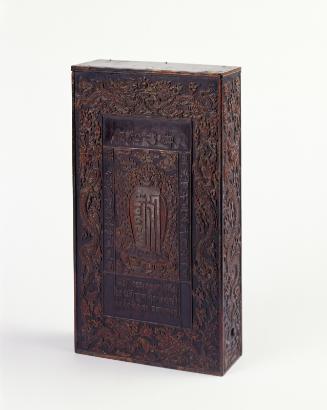

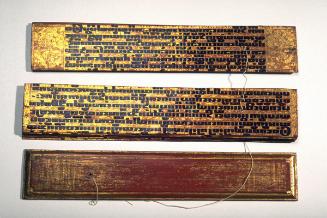

Cover for a Buddhist manuscript

- China

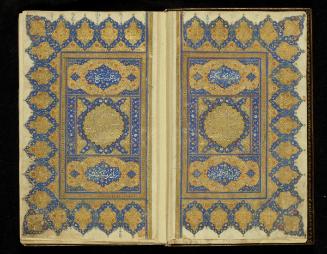

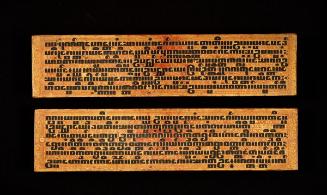

Tibetan Buddhist Texts

Tibetan Buddhism’s textual corpus is immense and encyclopedic. It contains early material from the Pali Canon, arguably the most ancient stratum of Buddhist literature. In addition, it contains texts from the Great Vehicle or Mahayana, especially the Perfection of Wisdom, whose ideas define the dominant philosophical perspective in Tibet. Finally, it contains texts called tantra that describe the visual and philosophical meditations of the Vajrayana, or Lightning Vehicle. Whenever they may have come to light historically, however, practitioners understand all of these texts as composed by the Buddha himself, but held back until the right circumstances presented themselves. In addition to texts understood as the Buddha’s direct teachings, called the Kanju, there is an equally immense body of commentarial literature called the Tenjur. Although different recensions differ somewhat in size, depending on texts included and mode of typography, they comprise, by some estimates, 332 volumes.

Tibetan writing was invented specifically to help standardize the translation of the Indian language of Sanskrit into Tibetan. The process took place in two waves, the first by the Ancient or Nyingma order, and the second by the New or Sarma orders.

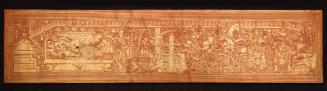

Tibetan Buddhist texts are written on stacks of leaves turned forward from front to back as the text is recited. As befits their sacred character, they are usually protected by wooden covers. These covers, whose incised decoration can be quite ornate, often bear inscriptions that tell us the text they were intended to contain.

During the Cultural Revolution, estimates suggest that approximately six thousand monasteries and their extensive libraries were destroyed. Some, however, survive in museums and private collections. The Asian Art Museum conserves one very early text that had been rescued from ruined Shalu Monastery—home to Buton, famous fourteenth-century compiler of the Tibetan Buddhist canon.